In the dynamic world of ecosystems, water plays a central role. The sensitivity of vegetation to drought, especially, hinges upon understanding water limitation. However, in trying to unravel this complex relationship, the scientific community has often been hamstrung by the immense variety of vegetation types, different climates, and the unpredictability of root zones. Our recent study in New Phytologist, titled Diagnosing evapotranspiration responses to water deficit across biomes using deep learning, sheds light on some of these open questions, but it also highlights where the knowledge gaps remain.

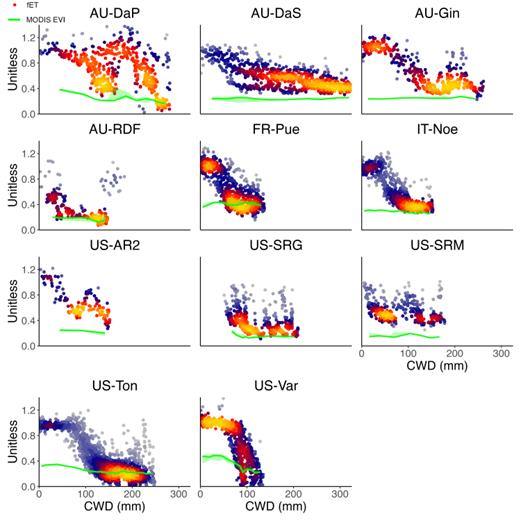

By employing deep neural networks, we’ve taken a closer look at how vegetation responds when faced with drought conditions. We’ve been able to isolate and measure a water stress factor (fET) that indicates evapotranspiration (ET) reductions during drought. Notably, our results have shown varying ET responses to water stress. From the rapid decline of fET in some savannah and grassland sites to the subtle reduction in most forests, the range is broad. But here’s the catch: in most arid sites, after an initial drop, the relationship between fET and the cumulative water deficit seems to level off (Figure 1). But why?

When initially presented with these findings, we wrestled with the question: was this due to increased xylem resistance at these sites, or could these locations access deeper underground water reserves? The answer, or at least a part of it, was found in previous field studies. These studies revealed that vegetation, especially in drier areas, can sustain ET during drought due to groundwater or deeper soil moisture access. At the same time, plants also strategically adjust their stomatal closure based on the progression of water deficits. However, many conventional land surface models don’t account for these intricacies, leading to an incomplete understanding of water stress and its impacts.

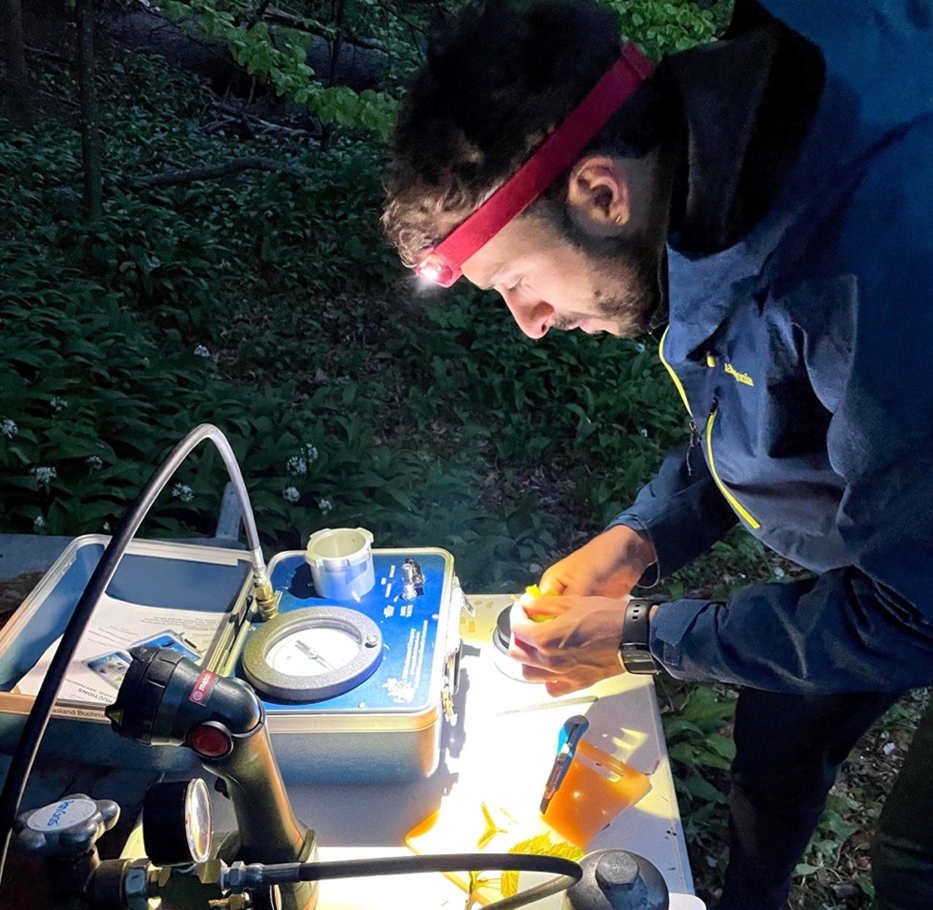

And this brings us to a critical gap. Despite their undeniable importance, field studies and measurements, particularly those focusing on water potential (Figure 2), are not easily accessible and not commonly co-located with ecosystem-scale measurements. This lack of data poses challenges for researchers aiming to refine global understanding of water limitation in terrestrial ecosystems.

Imagine the breakthroughs possible if researchers had access to a standardised and comprehensive database of water potential measurements across various biomes! Our exploration into ET responses to drought using deep learning has shown promising results. But the road ahead requires collaboration, shared resources, and a concerted effort to fill the data gaps. The scientific community would greatly benefit from a global network of water potential measurements, giving us the tools to better understand our planet’s ecosystems. To contribute your water potential data to this effort, visit ‘Get Involved’ and ‘Submit Data’.

Footnotes

R package ‘LSD’ was used to plot the point density (Schwalb et al., 2020)↩︎